A Spanner in the Works: The extraordinary story of Alice Anderson and Australia’s first all-girl garage by Loretta Smith

On the evening of 6 August 1926, Alice Anderson donned her driving goggles and gloves, waved to the cheering crowds outside Melbourne’s Lyceum Club, and got into her tiny two-seater Austin 7. With her former teacher Jessie Webb beside her, the boot packed with two guns, sleeping bags, a compass, four gallons of water, a supply of biscuits, and, strangely, two potatoes with red curly wigs, she tooted the horn and set off. Her mission? A three-week pioneering trip to the never-never. ‘There is only one main route from Adelaide to Darwin, and that is only a camel track,’ the tiny young woman behind the wheel said breezily of the 2,607-kilometre journey ahead of her. ‘We are not going to stick to the beaten track.’

When historian Loretta Smith first came across a brief snapshot of Anderson in a biography of legendary garden designer Edna Walling, she was intrigued. At twenty-nine, Anderson had already crammed several incarnations into one short life: mechanic, inventor, entrepreneur, owner of Australia’s first all-women garage, and the first woman to provide a private motorised service to the public, but she was missing, like so many other pioneering women, from the pages of Australian history. Who, Smith wondered, was this rebellious, contrarian force of nature, ‘small and pugnacious’ as her family described her? In A Spanner in the Works, Smith brings Anderson’s outsized story to colourful life via an archaeological trawl through university archives, intimate letters, and interviews with relatives.

Anderson was born in 1897, and her love of speed emerged early. At the age of ten, she was flying along on her aunt Isabel’s bicycle; at twelve she was galloping through bush near the family’s run-down cottage in Victoria’s rugged north-west.

The so-called horseless carriage story had begun a little over a decade before Anderson’s birth, with Karl Benz’s unveiling of the first petrol car in Mannheim in 1885. By 1915, the year she slid behind the wheel of her birthday gift, a shiny, eight-seater Hupmobile, Australia’s motor-vehicle population had reached 38,000, representing one of the world’s quickest uptakes of car ownership at the time. As Smith writes, driving was aligned with notions of freedom, independence, and exploration – a seductive idea in such a vast country.

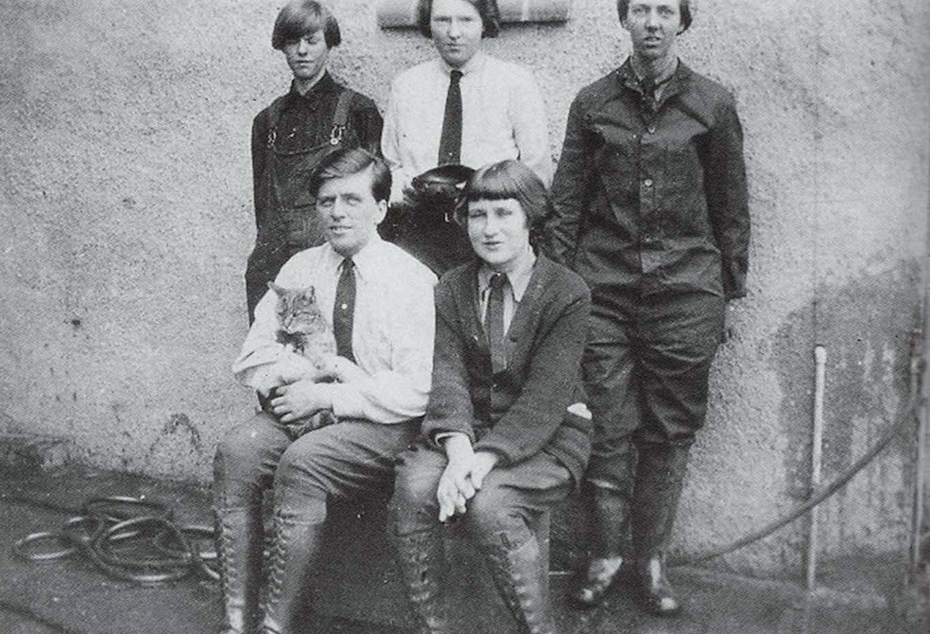

Five of Alice's garage girls pose outside, 1925. From left: unknown, Ruth Snell, Heather Buchanan, Marie Edie, Peggy Bunt.

Five of Alice's garage girls pose outside, 1925. From left: unknown, Ruth Snell, Heather Buchanan, Marie Edie, Peggy Bunt.

Women were not immune to this message. So-called ‘lady motorists’ were a new cultural phenomenon, despite a male backlash against female mobility (a letter by the Automobile Club Victoria’s solicitor arguing that ‘women drivers lack the nerve and judgement of the stronger sex’ was typical of the prevailing sentiment). Ground-breaking women motorists like French motorsport star Camille du Gast and British speedster Dorothy Levitt were busy proving men wrong from the 1900s onwards. Anderson was determined to join this intrepid band. She first learnt to drive lumbering char-à-bancs on the treacherous Black Spur before setting up a private chauffeuring service from her landlady’s backyard in Melbourne’s Kew. Wearing breeches, boots, a shirt, and a tie, she was often mistaken for a boy. Her clients came from Melbourne’s moneyed class; she drove them to the opera and theatre, scenic bush spots, and shopping expeditions on Chapel Street.

In 1919, Miss Anderson’s Motor Service, an all-women garage staffed by a band of handpicked and trained garage girls, opened with a launch party including the likes of a young Robert Menzies and Dame Nellie Melba. The press breathlessly charted the rise of this ‘boyish-looking figure in dungarees generously ornamented with very real grease’; the deeply conservative Melbourne establishment, unsettled by her bold flouting of social and gender codes, murmured darkly about sexual ‘inverts’ and moral transgressions.

It is a strength of this book that Smith weaves Anderson’s story so adeptly into this wider tapestry of sexual politics, cultural mores, and the development of feminism in 1920s Australia, although feminist motoring historian Georgine Clarsen believes Anderson was part of a generation of ‘radical individualism’ prizing individual accomplishments over gender difference.

Flipping a defiant finger at the naysayers, Anderson trained more than thirty young female chauffeurs, invented a trolley device that would later be copied to global success, and led touring parties to South Australia, New South Wales, and Tasmania.

Then came that historic trip to Australia’s Dead Heart. Crowds cheered as the tiny Austin, covered in red dust, chugged into Alice Springs. Here, Anderson would cross paths with young British pioneer aviator Alan Cobham. It was a serendipitous meeting; back in Melbourne, she had already begun plans to attain her pilot’s licence. As Smith writes, ‘Alice was ready to fly above the clouds.’

A mere week later, however, Anderson was dead. On a Friday evening, 17 September 1926, two of her garage girls found her bleeding from a gunshot to the head. A coronial inquest concluded that her death was accidental, but Smith suggests that this is far from the complete truth.

Smith’s mission was to exhume Anderson from history’s footnotes and to reinstate her as one of Australia’s true pioneers, but we are left with a sense of frustrating intangibility, a big question mark around this truncated life. Who would Anderson have gone on to become? What was her true destiny: motoring pioneer or daredevil aviatrix? Might she have become another Nancy Bird Walton?

As Smith writes, ‘the past can throw up fragments that raise more questions than they answer: pieces like a photograph or letters that tell part of a story, leaving us to guess at the rest.’

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.